Around Travis, we had to watch everything we said and did so as not to set off his Early Warning Uncoolness Alert System.

Fiction | Susan Sanford Blades | Issue 44

Of Monsters and Dolls

Lil was far too excited about her wedding-day Karla Homolka costume. Her eyes assumed a sadistic, possessive glint as she described the tacky veil and blonde wig she’d scored at Value Village. When she asked if I’d steal my mom’s industrial-strength hairspray to style the wig’s bangs, her irises floated to the northern hemispheres of her eyeballs—like Karla’s in her most sinister-looking photo, the one that had drenched the Edmonton Journal during her trial.

She doesn’t use it anymore, I said. You can have it.

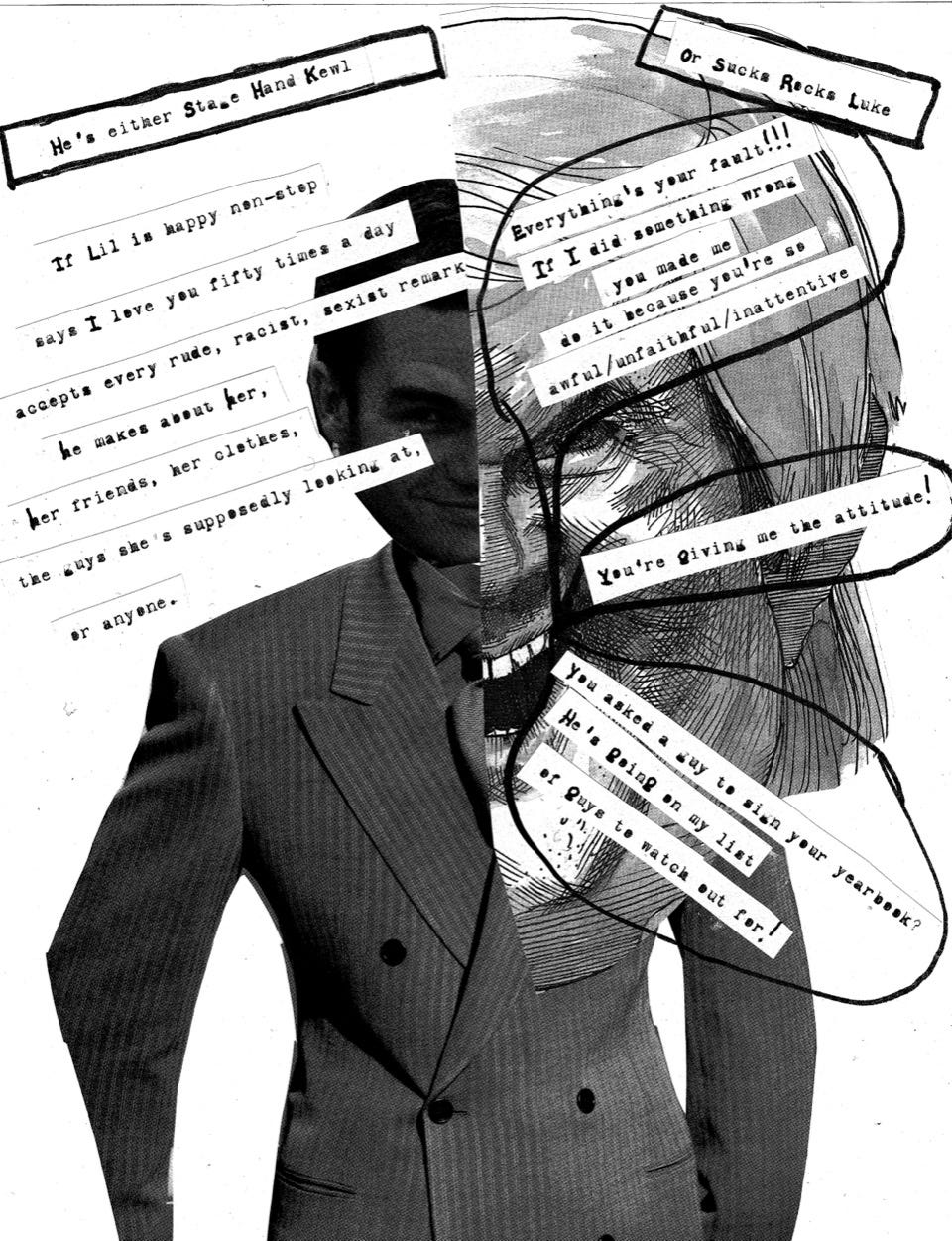

Lil nodded. She seemed deflated and this pleased me. I wanted to suck the air out of anything related to her newly formed union with Stage Hand Luke. Stage Hand Luke was supposed to be the pretentious boy behind the counter at Blackbyrd Myoosik whom we feared while in the store and ridiculed the moment we left. In the before-times, Lil would step with me onto the sidewalk outside the record store, lower her voice into monotone Adam’s apple territory, and say something like, That album’s good … if you’re into the sound of hyenas fucking.

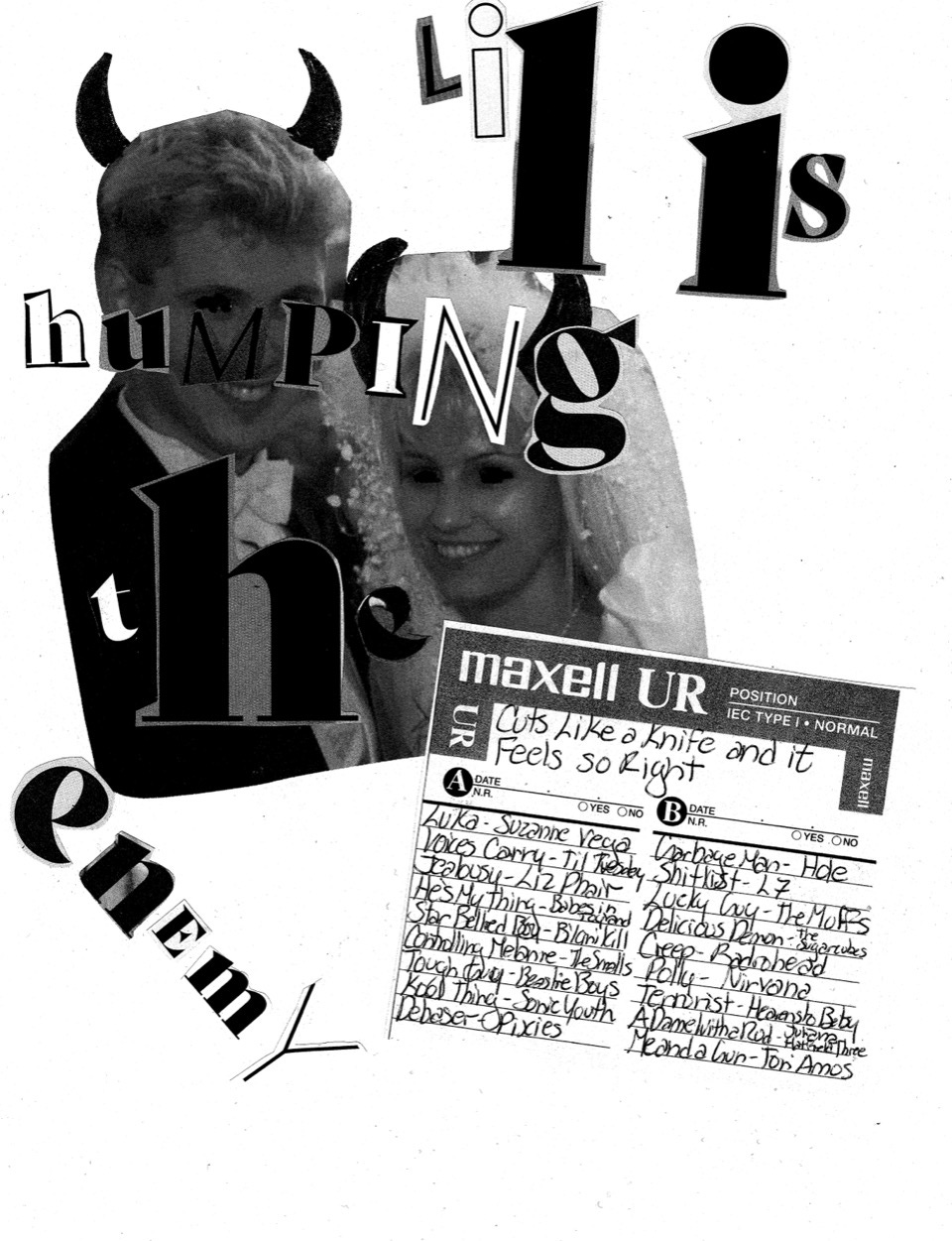

But since he’d winked at her at the Delores show, since he’d found out her last name in our Grade 11 yearbook, since he’d looked up her number in the White Pages, since he’d called three times pretending—in a high-pitched, nasal whine—to confirm a non-existent pizza delivery order and then called a fourth time and finally asked Lil to meet him for a cappuccino at Café La Gare—the smoking side—he was Stage Hand Luke no more. Once Lil became attached to him, we had to refer to him by his real name, Travis. Stage Hand Luke was Travis and Lil was Travis’s Girl and my world was tipped off its axis.

Since our Grade 10 year, Travis’s parents had taken a pilgrimage to Victoria at Hallowe’en to visit the site where Michelle, of Michelle Remembers fame, was possessed by Satan, thus leaving him home alone to throw an epic party. That year, he decided it would be murder themed and that he and Lil would dress up as Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka. Before this unfortunate coupling, I had planned to be the axe to Lil’s Lizzie Borden.

What should I be? I asked Lil.

Ted Bundy?

He just looks like a normal person.

Lil sighed. That’s the problem. They all do.

A Manson girl?

Lil grabbed my ankle. I got it, she said. You should be Tammy.

Faye Bakker?

No. Lil rolled her eyes. Homolka, she said. My little sister.

The one you killed?

Lil nodded. This is so sick. Travis will love this.

*

Travis was not Lil’s first foray into the boy kingdom. A line of boys had trailed Lil like paper Ken-dolls since she’d grown a pair of perfectly spherical C-cup breasts in Grade 9. At that time, the state of my chest was such that I could’ve still legally run topless through the sprinkler in my front yard. Lil picked up boys on weekends at Scona Billiards, one of three cool places underage kids could hang out in Edmonton—the other two being the dollar theatre on the outskirts of town and the river valley, accompanied by a book of matches and the two-six of Jack Daniel’s our fathers kept misplacing and replacing. Inevitably, the greasiest boy would slither like a ferret between pool tables to ask Lil out. Lil wasn’t choosy about looks. What she wanted was attention, power—the power to derail a boy’s pool cue, to divert beer into his windpipe, to cause him to fumble his footing and embellish his intentions so she’d dispense her seven digits to him. Sometimes, because I was the quiet friend, the glasses-wearing friend, the underdeveloped friend, their sweaty, acne-ridden sidekicks would ask for my number, assuming I was easy. I gave out the number for Lil’s mother’s womyn-centred naturopathic clinic. If they called, a receptionist named Meadow would greet them with, Hello, how may we serve your vagina?

But none of those boys had lasted more than a few weeks. None altered her the way Travis did. In his presence, she existed under a malevolent, disaffected rain cloud. This dreary haze smeared out anything about her that didn’t fit Travis’s idea of the perfect girl—an unlikely specimen who looked like Kate Moss, danced like Kate Bush and was not repulsed by Beavis and Butt-Head. Lil straightened her fuzz of ringlets so they hung like vertical blinds around her face. She looked perpetually like a sad Basset Hound. She exchanged her kinderwhore style—ripped tights enveloped by Mary Janes, babydoll dresses whose hems kissed the elastic leg seams of her underwear and whose buttons yawned open at her cleavage, near-dreaded hair scattered with brightly coloured plastic barrettes like bird berries in a dung heap—for Travis’s Indie-Rock style. Lil trawled Value Village for 80s hair metal band T-shirts she could wear ironically, she covered her planks of straightened hair with an oversized Oilers toque and she wore a pair of tight Levis whose threaded holes her ass cheeks bulged from like desperate inmates.

Around Travis, we had to watch everything we said and did so as not to set off his Early Warning Uncoolness Alert System. If we discussed Saturday Night Live, we could only appreciate the dry wit of Norm Macdonald and David Spade. If we talked punk rock, it had to be a band that had only graced college radio frequencies—the Sex Pistols were obviously sell-outs, as was Nirvana and any band that had ever been mentioned or covered by them. Any female musician was dismissed as a shrill neophyte who didn’t know her way around a tambourine, with the exceptions of Kim Gordon and Patti Smith.

*

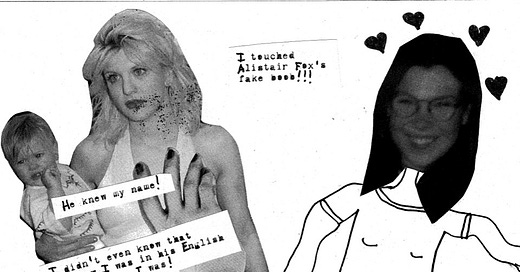

Since the end of August, Lil and I had spent Thursday nights working on our zines in front of my television, watching My So-Called Life. Lil’s zine was a third-wave feminist version of notches on a bedpost. In it, she’d rate the boys she’d slept with by comparing their penises to cosmetic supplies and the entire experience to a song. For instance:

Date: September 3, 1994

Date: Adrian

School: Ross Sheppard

Penis: between hairbrush and blow dryer

Sex: “Hey Ladies” meets “Crucify”

On our first Travis-era Thursday, Lil had wilted a little. Instead of digging into the tower of processed cheese slices I’d piled before us, she plucked a bag of celery sticks and a diet Snapple from her backpack.

What the fuck, Jessica Rabbit? I said.

Do you know how fattening those are? Lil pointed to my cheddar high rise.

Since when do you care?

You know that Grade 11 girl who’s like, translucent?

The one who looks like the mom from The Shining?

No, her friend. Travis used to date her.

Ew.

I’m a hippo compared to her.

Lil, you’re tiny.

Lil sighed and pointed a celery stick at the page in front of me.

You’re writing about Christian Hagen?

I slapped a processed cheese slice onto her empty page. How come you’re not writing about Travis?

I can’t rate him, Franny. I really like him.

Why?

Why are you sleeping with Christian Hagen?

Because he’s Christian Hagen.

What’s it like? Like, his penis. Lipstick tube?

As if. Curling iron? Like a big one.

Nice. Is he a good kisser?

We haven’t actually kissed.

He just like, puts his curling iron in you?

He kisses my neck.

That’s something.

I don’t know what’s normal.

You know what’s not normal? You, not cracking that hymen until now. Did you like, bleed in his new truck?

Oh god, what if I did?

It’ll be a souvenir.

Is Travis a good kisser?

He’s so tall it’s like this giraffe head is swooping down at me.

Sounds violent.

I feel like you don’t like him, Franny.

We both didn’t like him. Remember?

But now I do.

After that night, Lil stopped coming over on Thursdays, and as far as I know, she stopped making her zine. Travis forbade her from watching My So-Called Life because he didn’t like the idea of her drooling over Jordan Catalano, though he freely viewed Baywatch in Lil’s presence and commented on the movement of Pamela Anderson’s breasts as though they were a synchronized swimming routine.

Travis didn’t tear me and Lil away from one another so much as tease us apart, like strands of cotton candy. He made statements I couldn’t help but counter. He’d say, Who opened a can of tuna? when Alexis Jones—renamed Sexy Lexy after allegedly blowing the entire boys volleyball team—walked past, to which I responded: That’s right, Travis. Once a girl gives head, she smells like vagina. All. The. Time. Suddenly, I was labelled argumentative. A hairy-arm-pitted, penis-chopping witch Lil should steer clear of. Any warning I gave Lil, she would turn around on me. When I suggested she decide on her own musical tastes, she said, You’re the one who got me into riot grrrl. When I suggested she form her own opinions, she said, You’re the one who pushed that bra-burning bullshit on me. I was the problem, the guru behind our cult of two that Travis had freed her from with his open mind and his superior tastes. And maybe they were right. I questioned my closeness with Lil rather than his. I stepped back, let Lil go.

Lil spent lunch hours with Travis and his friends—known as the Head Hall kids because they’d inherited untouchable lockers from previous generations of burnouts in an exclusive, dead-end hallway that led only to the art room and the smoking cage outside. Every day at noon, they carried a Hibachi grill onto the track and barbequed a slab of flesh that had been marinating in one of their lockers all morning.

I spent those lunch hours with my Walkman, curled into a corner of chain-link fence outside the tennis courts that happened to be mere metres from Christian Hagen’s usual parking spot. Christian’s truck was a glimmering azurite among the dull trash heap of Uncle-Bob’s-old-Corolla-with-the-broken-tape-decks and other vehicles worthy of sixteen-year-old drivers and teachers’ salaries. Christian rarely visited his truck at lunch. I don’t know what the popular kids did at lunch. They existed on a separate plane in which they dressed like Brenda and Brandon even prior to that season’s first episode of Beverly Hills, 90210, where the girls dated university boys and the boys maintained non-monogamous long-distance relationships with Hula girls and Señoritas they met on summer vacation. They surely spent their lunch hours above the rest of us, dining in a magical Hard Rock Café in the clouds.

*

On the Wednesday before Hallowe’en—and I remember it was a Wednesday because that was the day of the week my mother always packed me an embarrassing sandwich of egg salad and sprouts stuffed between slices of crumbling pumpernickel—Christian approached me on the field in front of his truck.

Are you eating grass?

I squeezed the rest of my lunch into a Saran-wrapped log and tossed it behind me. Sprouts, I said.

Christian sat down, cross-legged, beside me. One of his thighs overlapped one of mine. There was a little square hole in the knee of his jeans, a heart drawn in black ink on his skin underneath. I felt jealous and then stupid. How had a few rides home, a few minutes with his stick shift against my spine, entitled me to possess this small plot of knee?

Going to Travis’s party, he asked.

Yeah. You?

Maybe.

I held my breath and wished for a fragment of his aloofness. To be the uncertain one.

I kind of hate Travis, I said.

Dude’s fucking weird.

Weird’s okay, I said. Just not … sexist pig.

Christian tucked his hair behind his ears and pierced his chin in the direction of the track, where Lil sat, knotted between Travis’s legs and submerged in his coat—an old Esso gas attendant’s jacket that looked like a crusty Muppet, split open, splayed and suffocated by nylon. He fed Lil bits of ripped chicken from his fingers like she was paralyzed from the neck down.

Would she let a sexist pig feed her, Christian asked.

Girl’s gotta eat.

You could kill him.

What?

It’s a murder party.

You want to kill anyone?

Christian laughed, a mono-syllabic, grunted heh. Is there anyone I don’t want to kill, he asked.

You should dress up as a serial killer. Jeffrey Dahmer?

Can I borrow your glasses?

I didn’t answer. If I ignored that comment, it would disappear from the transcript of my life. My glasses—that pox on my face, wrapping me in nerdiness—might also disappear. I longed for them to camouflage with my skin, to no longer be the novelty my classmates wanted to try on for kicks (Oh my god, you’re so blind!) like a bad wig at a costume store, to not be the first thing people noticed about me, the first thing they thought of when they thought of me.

I’ll probably just hand out candy with my mom, he said.

I couldn’t imagine Christian with a mother. I imagined a figurehead, a credit card, a woman who drank martinis, perhaps hiked up her pencil skirt and bent over a chaise longue at the Hotel Macdonald midday for her stock-broker lover. A woman who scolded Christian for trivial things, like a floor-dwelling wet towel, in order to feel maternal. I imagined Christian’s mother turned out the lights on Hallowe’en and bought vats of discount candy at the drugstore on the Day of the Dead to binge and purge on during sombre nights throughout the rest of the year.

You hang out with your mom, I asked.

We don’t like, party together.

But, you like her?

Sure.

He said it with an ease I resented. At eighteen, the grown-ups we liked were those who liked us back, liked who we were. My gut answer to that question would’ve been no.

Lucky, I said. I elbowed him. He held onto my elbow, tugged it into his hip. I felt the heat of his stare across my cheek. I turned toward him to find his eyes were not, in fact, gazing upon my cheek, but past me, behind me, scanning the schoolyard for potential witnesses, ensuring this token of tenderness would go unnoticed.

I moved my elbow from his hand.

Do you think it’s disrespectful to dress up as Tammy Homolka, I asked.

Is she that psycho figure skater?

No, she was the sister. Like, the one Paul Bernardo killed.

Right. Christian nodded slowly. I never thought to be a victim, he said. And he ran his fingers through his perfect shag of blond hair and sucked air through that perfect space between his front teeth—that tiny flaw that made him badass-sexy, like River Phoenix, as opposed to ugly-sexy, like the Night Stalker—and he said, Gotta go.

And I wanted him even more. And I resented him even more than that.

*

That Saturday night, I left the house red-faced and blonde. I stained my left cheek to match the chemical burn on Tammy’s face I’d seen on the news with a tiny jar of red currant jelly my mother had acquired ages ago on vacation in France. The jam was called Bonne Maman—good mother. She kept these jam jars in a row on the top shelf of a cupboard, untouched, like the lonely paint pots of an artist who’d lost her inspiration.

My mother drove me to Travis’s. My father would not be yanked from Hockey Night in Canada when the Oilers put blades to ice.

Are you and Lil dressing as Betty and Veronica again, she asked.

No, I said.

It was best to keep my mother entirely uninformed. If I so much as led her to a peephole into my world, she’d lean in with her vampiric thirst for information until she could discern a wide scope—every detail a potential liability, evidence she’d use against me on crueler days.

Who are you going as?

My mother spoke tentatively. She knew I didn’t want to talk. I felt for her almost enough to give her a taste. She was me in the locker room, laughing on key with the popular girls as they whined about the D cup–inspired welts on their shoulders, covering up the double-A smoothness on mine. Me, laughing so as not to be caught not-laughing, to be found out as different, quiet, virginal. Glad to be a girl if only because we’d been trained in politeness, conflict avoidance, blindness to elephants in rooms. My mother was trying to feel a bit less alien from me. But a mother’s natural habitat is on the outside. A mother cares too much, worries too much, controls too much to know her daughter’s version of herself.

I’m a baby who fell asleep in her jam sandwich, I said.

Mmmh. Unique. What’s Lil being?

A serial killer.

That’s … different.

Lil’s different now.

My mother’s eyes narrowed. Not out of concern for my friendship with Lil, but because the car slipped on a patch of ice and veered slightly toward a parked car on the side of the road. She clenched the steering wheel, hands at ten and two in her leather driving gloves. She was a nervous driver, more so in winter conditions, and always reminded me of a woman careening toward revenge behind the wheel. Cruella De Vil in search of her puppies.

I don’t know my way around this neighbourhood, she muttered.

Take your next left. There’s a brown car out front.

As soon as my mother stopped the car, I reached for my door.

Frances, she said. Her arm hovered in the space between us, then she let it fall on the gear shift. She tapped her fingers on its knob like a bored typist.

How is Lil different? she asked.

I dunno, I said. She’s not, really.

I’d given my mother a three-word synopsis of my personal calamity and she’d let her anxiety behind the wheel take precedence. This seemed an unforgivable selfishness. But what if I had allowed my mother her uncertainty? What if I had known the extent to which my distance broke her heart?

*

Entering a party alone was one version of social hell. I couldn’t knock. Encyclopedia salespeople knocked. Mayoral candidates. Girl guides, with their cookies. This left me to slip in unnoticed and skulk like a shadow in the foyer.

I heard Lil. Not her normal voice, but her Travis-voice—a soprano mewl she sifted across her tongue in his presence. I peeked into Travis’s living room and saw her picking lint from his suit jacket, scratching her fingers through his ridiculous blond wig, like he was a silverback. The Head Hall crew surrounded Lil and Travis, passing around a bong. Gorillas in the mist.

The front door opened behind me. A pair of heels scraped across the tile. I didn’t turn, assuming the arrival of another Nicole Brown Simpson.

Lemme guess.

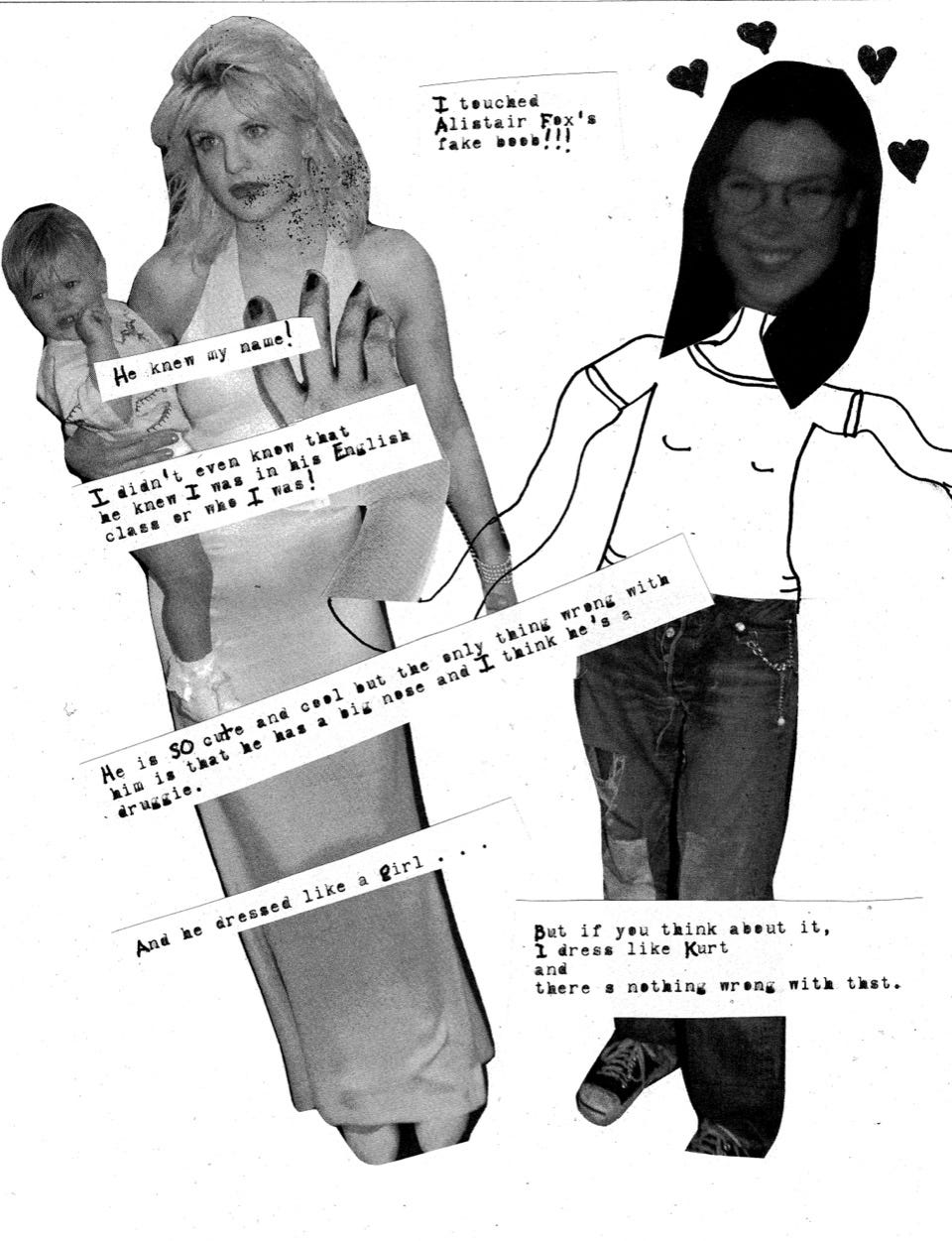

The voice behind me registered low. Male, definitely, with a bit of a smoker’s rasp and a soprano crack. I turned to see a boy dressed as Courtney Love at the 1993 MTV awards. White satin floor-length gown with a low V-neck, three-inch heels, dirty mess of bleached-blonde hair (black at the roots), maraschino lips, baby at the hip. Not a real baby, of course, but a Cabbage Patch Kid dressed in white and yellow like the original Frances Bean. He was not impersonating a woman in an over the top, balloons-up-the-shirt, comedic way like most boys would. He embodied femininity with this carefully curated look—intricate, sexy in its subtlety—deceived only by the definition in his biceps, his Adam’s apple, the lack of dip before his hips, his figure more horse than pear.

Are you JonBenét Ramsey after a make-up mishap, he asked.

Tammy Homolka after a Halothane mishap.

Even creepier.

When he smiled, the left side of his upper lip lifted higher than the right in an Elvis-style curl I felt like a hot palm to my crotch.

You’re in my English class, I said.

In English, I sat directly across from that mouth. Alistair Fox’s mouth. While Christian hosted a rugged, cowboyish, sandpaper-lipped mouth, Alistair’s was voluptuous and soft, a deviation from the expected. I’d spent many an hour covertly staring at his lips—head angled downward to the copy of Hamlet open on my desk, eyes tilted up above the rims of my glasses toward his extended Cupid’s bow, to the pencil eraser he rolled across it while our teacher dissected the question of being.

Yeah, he said. Frances?

I could not believe he knew my name. Alistair Fox was a self-confident outcast. Beyond cool. Beyond popular, beyond grunge, altie, earthy, neo-hippie, metal-head, track star. Beyond high school. He appeared at English rarely—never on time and always unapologetic. He existed in a world outside of that bubble gum microcosm—a world in which Travis was a sad, lonely autodidact in the school of punkology, middle aged and eating from a can in a basement suite, banging on the ceiling with a broom handle when his neighbours played their Top-40 radio over his art noise.

Alistair led me to the kitchen and drew me a cup of beer from the keg. We lined the kitchen island alongside a few Marcia Clarks and a possible Ted Bundy. I took the living room–facing angle so I could see if Lil noticed me getting on alone. And she did. Lil could smell exclusion like an oncoming rain. She turned toward the kitchen, smiled at me and waved. She lifted Travis’s hand from around her waist and stood up. She still cared enough to not let me experience anything without her. I still mattered. But Travis tugged on Lil’s wedding dress and said something, who knows what, it didn’t take much, to divert her attention back to him, to make her sit down again.

Alistair and I stared at each other. The wheel of conversation topics spun in my mind.

You look good as a girl, I said.

He puckered his lips and thrust a hip out from the island we leaned on.

Does this mean you think Courtney killed him?

It’s a commentary on the conspiracy theories, he said.

Cool.

Honestly, I saw this dress at Value Village and I was being Courtney no matter what.

How did you do your boobs?

Bags of Jell-O in a bra, my love.

Can I touch one?

Alistair unfurled his shoulders, arched his back. I poked at one of his squishy breasts.

Feel it, he said.

With the tips of my fingers, I gently petted the curve of his breast. I squeezed it, felt the jelly between my fingers. Then I cupped his Jell-O breast in my palm and coaxed it upward, circled my thumb around an imagined nipple. Alistair moaned—a startled high-pitched mumble. I held his gaze—something I didn’t do often. I siphoned my desire into this disembodied sack of jelly. Strange enough to be erotic but less alien than a penis—that anthropomorphous and unpredictable boy part, that portal to the sexual point of no return, that harbinger of HIV and babies. I wondered if it hurt him, his penis strangled and engorged between his thighs, and if he considered me worthy of that pain. Alistair stuffed all of his fingers into the back pockets of my GWGs. We hadn’t even kissed. He poured over me and sighed heat into my ear as I kneaded his breast.

The party continued like a carnival around us. I heard the front door open and the shuffling, squeaking, skidding feet of a parade of boys. Then, the call of a random jock: They’re lezzing out!

I dropped my hand. Alistair and I straightened, retreated from one another. A popular boy—the captain of the hockey team, one of Christian’s crew—stood before us, pointing. Then came the squawks from the rest of them, like magpies scrapping over a dropped slice of salami. Where? Where? Where? I froze—my fight-or-flight reaction. My body is a vessel for the soul of a squirrel, reincarnate.

Alistair, on the other hand, perhaps a snake. He slunk onto one elbow and projected out the side of his mouth, Yeah, where are those lesbos?

The hockey captain squinted at Alistair and yelled, It’s a dude.

Christian’s friends stampeded into the kitchen. I scanned the crowd for Christian. Amid all the commotion, what could have been a life-or-death situation for Alistair, I only wanted Christian to see me touching another boy. But he wasn’t there.

Alistair continued to slither around the problem. He asked me if I’d finished 1984.

We’re reading Hamlet now, I said.

The hockey boys migrated toward us. My stomach tightened. Alistair smiled into his beer.

Hey, fag. The hockey captain stood about a metre from us, flanked by several teammates.

Alistair maintained his gaze on me. Hamlet, eh? I guess I should go to English more.

I wanted to tell him to run—he’d already dropped the option to hide like the rest of us, to camouflage until high school was over.

The captain wobbled closer. He had a menthol aura, so drunk his edges smeared into the landscape.

Hey. He poked his pointer into Alistair’s exposed cleavage. Faaaag.

Travis and the Head Hall crew entered the kitchen and formed a semi-circle across the island. They were there as spectators, laughing and elbowing each other like this was a Saturday Night Live skit. These boys were artists, music lovers, punks. They lived on the outskirts of normalcy. The bits of muscle roping their bones were there by the grace of testosterone and accidental activity. Aside from Alistair, they were the most effeminate boys standing. And a coward will rally against his nearest weakness.

Lil swayed at Travis’s side like a tipsy bowling pin. Travis, do something, she said.

Take a pill, he said. It’s fine.

The hockey captain smacked a meaty hand onto the island where Alistair’s hip rested. He slid a foot between Alistair’s, his leg tight against Alistair’s crotch. The back of his leather hockey jacket smothered me with the scent of rancid sweat and Old Spice. He tilted his chest into Alistair’s chin, leaned his lips within a breath of Alistair’s throat and said it again.

Hey, fag. You like that, fag?

The hockey boys flocked to their captain’s side, pecking an absurd chorus of Hey, fag at Alistair. He had no clearance to wield his weapons—sarcasm, indifference. He raised his arms, I assumed to wilt into a fetal ball and cower, which is what I would’ve done. But Alistair thrashed his arms outward, scythed himself an expanse through which he told them all to fuck off.

Travis, Lil said again. Do something.

The front door banged open, and Christian stumbled through. He gave the wall a high-five to steady himself and pin-balled between furniture and party-goers toward the kitchen as though he was trained to sniff out beer kegs and burgeoning fist fights.

Alistair strode past the hockey captain, deliberate and regal. More Princess Di than Courtney Love. I retrieved Alistair’s Cabbage Patch Kid, which lay face-first on the tile floor, and offered it to him. He tucked it into the crook of his elbow without shifting his focus my way. This felt like a huge slight, as though I’d saved his real baby. As though I could’ve performed no greater act of solidarity.

Mid-stride, Alistair lurched, restrained by the fabric of his dress. The hockey captain had stepped onto its hem. The white satin stretched taut against Alistair—his hula hoop ribs, his jujube belly button. I scanned his crotch in an effort to discern how he’d tucked himself away.

Alistair spun and whipped that hard-plastic Cabbage Patch Kid face into the hockey captain’s. Got him right on the bridge of his nose.

Christian shuffled into the kitchen just as the captain bounced back and swung a fist. He punched Christian in the ear. Christian deflated to the kitchen floor. Alistair ran. The hockey boys huddled around Christian, their broken, golden boy.

Travis, Lil said. We should make sure he’s okay.

Travis nodded that time. He weeded a bag of peas out from his freezer and offered it to Christian. You okay, dude, he asked.

Not him, Lil said. It’s freezing outside. That guy ran out in his dress.

Travis laughed. Anyone seen a mink coat?

Let’s go check on him, I said to Lil. I reached my hand toward her. She unlatched herself from Travis and followed me out the front door.

Where are you going? Travis yelled after us. That pussy’ll be fine.

By the time we slammed Travis’s door behind us, Alistair was out of sight. His high heels had left prints, stamped into a thin layer of snow like deer tracks in a straight line out of Travis’s cul de sac.

*

A new snow still excited us in the manner of freshly poured concrete. Our canvas, our night. Lil and I scuffed snow angels in the middle of that dead, suburban street. Lil sacrificed a warm finger from inside her coat sleeve to emblazon an electrical box with TRAVIS IS A CHEEZY TURD. I spread my coat for her and she stuffed her hand under my shirt and into my armpit. I squeezed her fingers with the flesh of my arm, the way we used to warm ourselves after tobogganing down the slanted streets of our neighbourhood, or after snowball fights with the kids next door. Two girls, cross-legged among a puddle of mitts, toques and snow pants, our hands wedged into each other’s armpits as though channelling a sacred warm sisterhood through our mammary glands.

Lil retracted her hand and smelled the tips of her fingers.

I missed you, she said.

You’re so gross.

You’re the one who has mega BO.

Lil grabbed my hand, and we carefully stepped through the snow out of Travis’s neighbourhood.

Are you going to break up with him, I asked.

Lil walked with me in silence, the rubbery crunch of snow beneath our feet. We arrived at our bus stop—a Plexi-glass beacon on the freeway overpass. Lil stared across the freeway from where we stood, toward the stadium-bright lights that flooded our local ski hill.

If he doesn’t apologize, she said.

Lil had never been with a nice boy. She didn’t understand that a domineering boy can apologize, but he’ll never be sorry. I knew she’d stay with Travis. Maybe she admired his ability to manipulate the manipulator. Maybe she wanted a break from constantly feeling too bossy, too bitchy, too slutty. If a boy could control her, own her, she could let go, relax into that possessive hand-holding charade. Maybe she liked seeing herself reflected in Guns N’ Roses videos. Maybe, in that coupling, she finally felt tangible to herself, valuable to the rest of the world.

The freeway dove down the slope of the ski hill to its valley and resurfaced at a glowing overpass about a kilometre away. Under the spotlight of a streetlamp, a small white figure scurried across a dusting of snow.

How far do you think he has to go, I asked.

Travis?

I shook my head, extended a finger toward the light. Will they get him on Monday?

They’ll forget this by morning.

Will you?

Lil fixated on the radiant ski hill, that enticing white light, as though waiting for something to compel her out of a trance.

Girl on Paper

“Of Monsters and Dolls” is the second chapter from a novel manuscript entitled Girl on Paper. It’s an episodic novel that follows our protagonist, Frances O’Neill, through her Grade 12 year. Each chapter takes place during one month of the 1994/95 school year. Frances is into riot grrrl and makes a zine, so after each chapter of the novel, which is told from a first-person retrospective point of view, there’s an issue of Frances’ zine, which is more of a raw, visceral diary entry. Frances is adopted, and spends the novel trying to connect with her birth mother, so this book is about mothers and daughters, but mostly it’s just about being a teenaged girl in the 90s.

Susan Sanford Blades lives on the territory of the Lekwungen peoples, also known as the Xwsepsum and Songhees Nations (Victoria, Canada). Her debut novel, Fake It So Real, won the 2021 ReLit Award in the novel category and was a finalist for the 2021 BC and Yukon Book Prizes’ Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize. Her short fiction has been anthologized in The Journey Prize Reader: The Best of Canada’s New Writers and has been published in literary magazines across Canada as well as in the United States and Ireland. Her fiction has most recently been published in Gulf Coast, The Malahat Review and The Masters Review.

Support Send My Love to Anyone

Support Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

Connect

Bluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA