Corinna Chong | Issue 33

"Ambiguity is one of the distinguishing characteristics of the literary works I most admire."

In Defence of Ambiguity

My short story collection, The Whole Animal, begins with an epigraph taken from an interview with the great photographer, Sally Mann. When discussing what she strives for in creating a photograph, Mann says, “If it doesn’t have ambiguity, don’t bother to take it.” I first came across this interview when I was an eighteen-year-old, fresh-out-of-high-school university student, and it has stuck with me ever since. Hearing it set off a spark in me, though I didn’t fully understand why at the time. I felt strangely seen, as though Mann had articulated something I had always known to be true but had never been aware of until I’d heard it acknowledged. It became a guiding principle for the way I look at art and the approach I take to my own writing.

Indeed, ambiguity is one of the distinguishing characteristics of the literary works I most admire. One of my favourite short stories of all time, and one I often teach in creative writing classes, is Lorrie Moore’s “How to Become a Writer.” One reason I like to teach it is for the clever trick it plays on readers with its title, which suggests that what follows will be instructional and methodical, like a manual, only to initiate instead a fragmented second-person narrative charting the protagonist’s unlikely journey toward becoming a writer—a journey full of self-doubt and debilitating uncertainty. The surprise of this is refreshing, but also unsettling for the reader. Another reason is the ending. In the closing paragraph, the protagonist, Francie, having embraced the self-punishment that being a writer entails, describes what her life has become:

Occasionally a date with a face blank as a sheet of paper asks you whether writers often become discouraged. Say that sometimes they do and sometimes they do. Say it’s a lot like having polio.

“Interesting,” smiles your date, and then he looks down at his arm hairs and starts to smooth them, all, always, in the same direction.

In the most recently published version of the book, this closing paragraph happens to fall at the end of the page. My students often ask if that’s really the ending, or if perhaps I accidentally missed a page in the photocopy. Surely that can’t be the actual ending, they often say. What follows is a discussion about the possible reasons for this choice, which inevitably involves a careful analysis of the diction, phrasing, and imagery. Not only do these final lines evoke Francie’s continued (perhaps even growing) inability to connect with the world outside her stories, but they seem emblematic of the monotony and predictability of these real-world encounters. The structure of the final phrase, particularly the resonance created by “all, always” is notable and certainly intentional. Moore seems adamant to emphasize the repetitive pattern of the smoothing action, which, if you want to stretch, could speak to a kind of conformism that is constantly being pushed upon Francie by her mother, her roommate, her classmates in workshop. But writing for Francie is an act of quiet resistance—one that, ironically, she doesn’t even seem to have control over. Ultimately, Francie isn’t striving to become a writer; rather, despite her desperation to “be something, anything else,” she cannot help but become a writer.

For me, this is the perfect kind of resolution for a short story. I think the best short stories end with a sense and a rhythm of finality, but resist giving tidy fixes to the problems the characters face. Instead, they shine a light on the layers of meaning that the writer has built across the story as a whole, and bring us to a new level of understanding of the profound complexity of the story’s central conflict. I get immense joy out of being able to discuss at length the potential implications of the final lines of a story; when I do this in the classroom with my students, I can sometimes see their eyes light up with the realization that wow—a few words on the page have the power to truly move us as readers, to make us think and feel so deeply!

Stories like Moore’s are the inspiration behind the way I approach endings in my own writing. My hope is to give my readers the same kind of feeling that Moore gives me—a rush of goosebumps as I read the final lines and marvel at how richly and carefully constructed the story is.

I concede, however, that not everyone appreciates endings like these. I hear the term “open-ended” often applied with derision to books or movies that resist tidy conclusions. Some readers, it seems, feel cheated when they encounter an ending that leaves too much to interpretation. The criticism is often that the writer “didn’t know how to end it,” or got lazy by the time they reached the end. It’s difficult for me not to take offence to comments like these, even when they’re directed at someone else’s work. While, of course, I’ll admit that there are plenty of bad endings out there, I would argue that rather than being unskilful or lazy, some of these endings are intentionally and painstakingly designed to resonate with ambiguity. Ambiguity, in my view, is different from vagueness. A vague ending is murky, tentative, and abstract, and fails to indicate a change of state. Thus, it feels stagnant, like a rock dropped into a swamp. In contrast, an ambiguous ending feels like a bird taking flight. It lifts off into new territory, charged with possibility, but respects the reader enough to let them envision what that territory could look like, based on what the story has already offered them. An ambiguous ending lets uncertainty stand as something valuable and meaningful in its own right.

More recently, I’ve come to realize that my impulse to defend ambiguity goes much deeper than I had initially realized. I think part of the reason that Sally Mann’s words struck me so deeply as a young adult is that ambiguity has always been a central part of who I am. As a biracial person, I learned from a young age that ambiguity is unsettling for most people, and therefore often treated as a problem to be solved. I grew accustomed to being questioned about my race whenever I met new people. What are you? they would often ask, or, the slightly more sensitive, Where are you from? When I’d reply that I’m Canadian, the questioner would shift gears with additional questions, eventually gleaning the information that satisfied them: my dad is Chinese, my mom is German. The conversation would often end with some expression of satisfaction that the truth had finally come to the surface, or an explanation like “I thought maybe you were Hawaiian/Filipino/Inuit,” etc. As a child, I often came away from these exchanges feeling intensely awkward and alienated. I hated that my appearance inspired people to probe me with questions, as though I wasn’t allowed to simply exist as someone whose race couldn’t be immediately pinned down.

I like to believe that multiracial kids today no longer get questions like these. After all, multiracial families are far more common these days than they were when I was growing up. But at the same time, I think the assumption that any kind of ambiguity is problematic prevails, and has its roots in the narrow way of seeing I faced as a child. I believe that the fact that people continue to be uncomfortable with ambiguity makes it imperative for artists to keep exploring it. After all, what is art for but to challenge us, to take us out of our comfort zones, so that we can gain a richer understanding of and empathy for experiences that lie outside our own?

An integral part of my growth as a writer and as a person has been coming to the conviction that there is, in fact, great power and beauty in ambiguity, and that finding a way to communicate this through my writing—to intentionally cultivate an uncertainty that can stand as an authentic encapsulation of the story as a whole—is a worthy goal. I won’t claim that I’m even close to mastering this in the ways that Sally Mann and Lorrie Moore have, but, like Francie in “How to Become a Writer,” trying to do so has become an act of resistance that undergirds the fundamental reason why I write: to illuminate the complexity of human experience, and thereby challenge the idea that all stories should be molded into an immediately recognizable shape.

I would even go so far as to say: if it doesn’t have ambiguity, why bother?

Works Cited

Moore, Lorrie. “How to Become a Writer.” Self-Help. Vintage, 2007, pp. 117-26.

“Sally Mann in ‘Place.’” Art21, 21 Sep. 2001, https://art21.org/watch/art-in-the-twenty-first-century/s1/sally-mann-in-place-segment/.

Corinna Chong‘s first novel, Belinda's Rings, was published by NeWest Press in 2013, and her reviews and short fiction have appeared in magazines across Canada. The Whole Animal, a collection of short stories, was published by Arsenal Pulp Press in 2023, and includes “Kids in Kindergarten,” which won the 2021 CBC Short Story Prize, and “Love/Cream/Heat,” which was selected for The Best Canadian Stories 2024, published by Biblioasis. Bad Land, her second novel, will be released in Fall 2024 with Arsenal Pulp Press. Corinna lives in Kelowna, BC and teaches English, creative writing, and fine arts at Okanagan College.

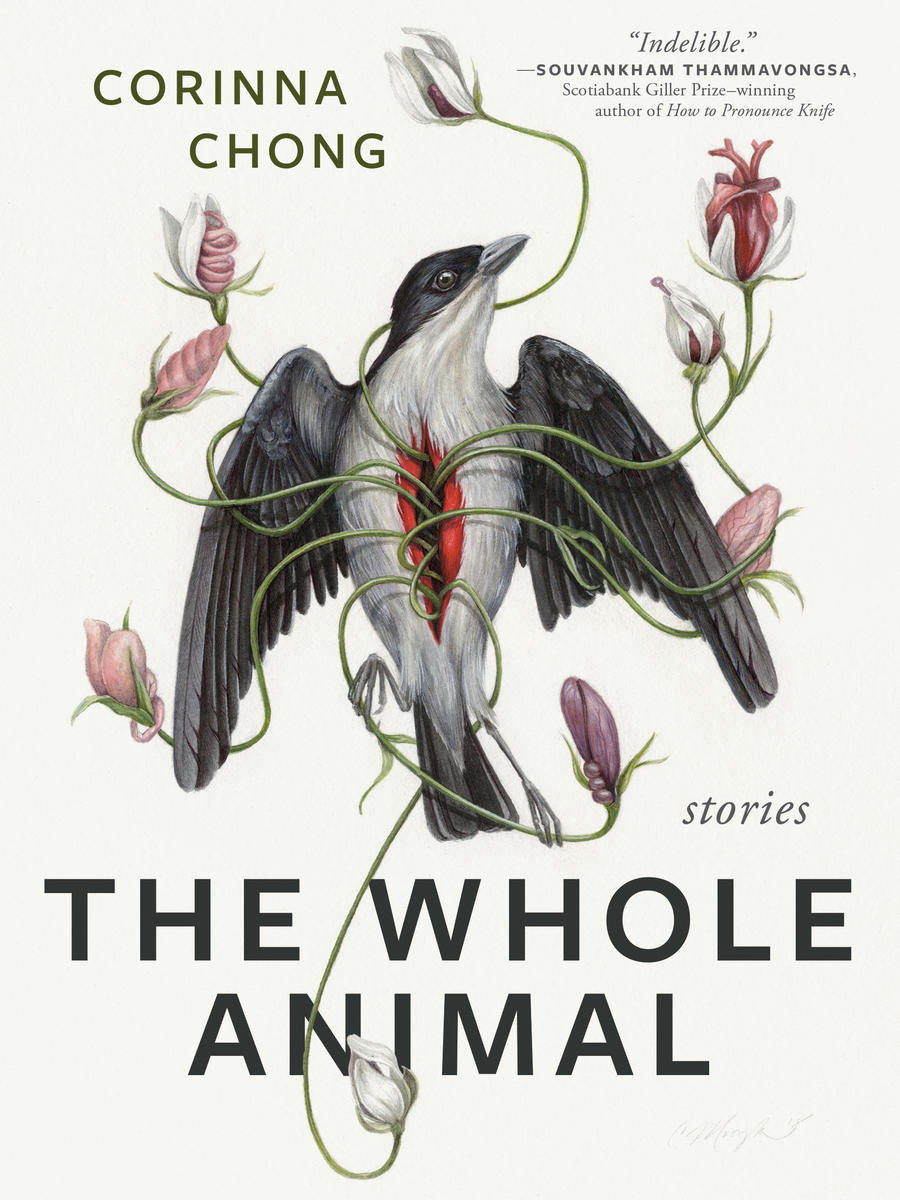

The Whole Animal: Stories by Corinna Chong Arsenal Pulp Press, 2023

A refreshingly original debut collection of short stories that grapple with the self-alienation and self-discovery that make us human.

For fans of Souvankham Thammavongsa, Lynn Coady, and Lisa Moore comes a striking debut collection of short stories that explore bodies both human and animal: our fascination with their strange effluences, growths, and protrusions, and the dangerous ways we play with their power to inflict harm on ourselves and on others.

Throughout The Whole Animal, flawed characters wrestle with the complexities of relationships with partners, parents, children, and friends as they struggle to find identity, belonging, and autonomy. Bodies are divided, often elusive, even grotesque. In "Porcelain Legs," a pre-teen fixes on the long, thick hair growing from her mother's eyelid. In "Wolf-Boy Saturday," a linguist grasps for connection with a young boy whose negligent upbringing has left him unable to speak. In "Butter Buns," a college student sees his mother in a new light when she takes up bodybuilding.

With strange juxtapositions, beguiling dark humour, and lurid imagery, The Whole Animal illuminates the everyday experiences of loneliness and loss, of self-alienation and self-discovery, that make us human.

Support Send My Love to Anyone

Support Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

Connect

Bluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

I really love this essay.