How do you measure artists’ labour according to this economy of labour?

Art | June Pak | Issue 5

Invisible Labour - 보이지 않는 노동 b

Visual artist June Pak examines invisible labour in her work.

We live in a society that values productivity; labour = productivity; productivity = (visible) products; products = money. How do you measure artists’ labour according to this economy of labour? Invisible nature of art-labour might be the cause as to why hours of my labour are not being valued as much as other types of labour. We proclaim that we love art, that we cannot live without it, and our society is better for it, but do we value the time and labour artists devote to it?

However, a sense of freedom and autonomy can be found in this invisible labour. Once my labour becomes visible, meaning there is an expectation of turning my labour into a profit, I am no longer in charge of my own work. There is a price I have to pay for my freedom. I have to keep my precarious part-time gig, so I can continue to wander and work at the same time.

In this book, I want to illustrate the complex web of invisible and visible labour that goes into making an artwork.

우리는 생산성을 중시하는 사회에 살고 있습니다; 노동 = 생산성; 생산성 = 뚜렷한 결과물; 결과물 = 돈. 이런 노동 경제 틀 안에서 예술가의 보이지 않는 노동은 어떻게 측정합니까? 보이지 않는 예술 노동의 성격이 다른 유형의 노동만큼 가치가 부여되지 않는 원인이 될 수 있습니다. 우리는 우리가 예술을 사랑하고, 예술 없이는 살 수 없으며, 우리 사회가 예술로 인해 더 좋아진다고 선포하지만, 우리는 예술인의 시간과 노동을 소중히 여기는지는 궁금합니다.

하지만, 이 보이지 않는 노동은 작가에게 자유와 자치권을 주기도 합니다. 내 노동이 눈에 보이게되는 순간, 내 노동을 이익으로 전환 할 것이라는 기대가 생기며 더 이상 나는 내 작업에 주인이 될 수 없는 우려를 감당해야 합니다. 난 내 자치권을 지키기 위해 계속해서 불안정한 시간강사 노릇을 하며 자유롭게 방황 하면서 일 할 수 있는 대가를 지불 해야지요.

복잡하게 연결된 보이는 또는 보이지 않는 예술 노동 과정을 작은 책자로 시각적으로 설명하고자 합니다.

This project Invisible Labour came about when I was invited to a group exhibition called Art_Bop* in Korea, Dec. 17, 2020 - Feb. 17, 2021. The exhibition is the first stage of a larger project that questions the value of art and labour, initiated by an artist collective by the same name based in Mullae Artist Village in Seoul. The neighbourhood Mullae is formed by a large cluster of independent metal fabrication shops. Artists started to move into the area because of the cheap rent. After over 10 years, the relationship between metal workers and artists generated a communality based on the precarious nature of shared interest in each other’s labour.

The fact that the exhibition took place in the Alternative Artspace IPO, one of the oldest artist-run centres in Mullae, marks a significant introduction to the debates on co-existing social, economic, and political conditions that art-labour must endure.

Exhibition Artists:

Kang MyungJa, Gwon YoungJa, Kim MiRyeon, Kim Jin, Daniel Kowalski, Moon HaeJoo, JiWon Park, MiRa Baek, Silvia Minni Wang HeeJeong, Im DongHyun, Lee MalYong, Jeong HaSoo, Cho SungHoon, Chun SoJin, June Pak, Choo YooSun, Choe RaYun

View the virtual exhibition here.

* Bop is a Korean word for a bowl of rice. The usage of the word “bop” is a lot more complicated than just a bowl of rice. Aside from being a daily staple, bop also connotes one’s well-being; it carries a meaning of care for each other; it is also used as a means to represent basic economic survival.

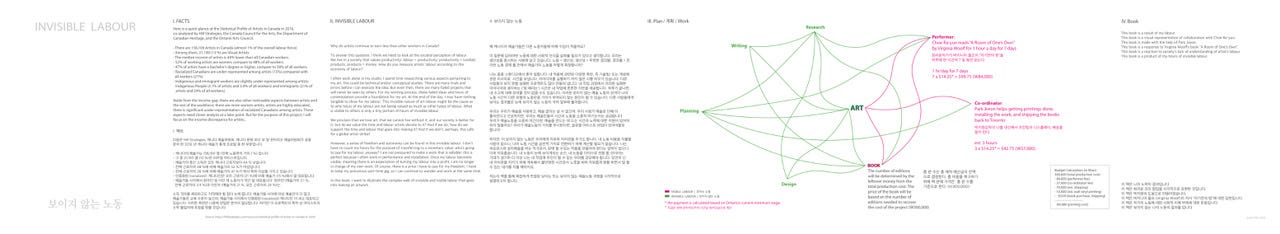

Invisible Labour Artist Book, Diagrammatic drawing

I. FACTS

Here is a quick glance at the Statistical Profile of Artists in Canada in 2016, co-analyzed by Hill Strategies, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Department of Canadian Heritage, and the Ontario Arts Council.

There are 158,100 Artists in Canada (almost 1% of the overall labour force)

Among them, 21,100 (13 %) are Visual Artists

The median income of artists is 44% lower than all Canadian workers.

52% of working artists are women, compare to 48% of all workers.

47% of artists have a bachelor’s degree or higher, compare to 28% of all workers.

Racialized Canadians are under-represented among artists (15%) compared with all workers (21%)

Indigenous and immigrant workers are slightly under-represented among artists: Indigenous People (3.1% of artists and 3.9% of all workers) and immigrants (21% of artists and 24% of all workers)

Aside from the income gap, there are also other noticeable aspects between artists and the rest of the workforce; there are more women artists, artists are highly educated, there is significant under-representation of racialized Canadians among artists. These aspects need closer analysis at a later point. But for the purpose of this project, I will focus on the income discrepancy for artists.

다음은 Hill Strategies, 캐나다 예술위원회, 캐나다 문화 유산 부 및 온타리오 예술위원회가 공동 분석 한 2016 년 캐나다 예술가 통계 프로필 중 한 부분입니다.

캐나다의 예술가는 158,100 명 (전체 노동력의 거의 1 %) 입니다.

21,100 명 (13 %)은 비주얼 아티스트입니다.

예술가의 중간 소득은 모든 캐나다 근로자보다 44 % 낮습니다.

전체 근로자의 48 %에 비해 예술가의 52 %가 여성입니다.

전체 근로자의 28 %에 비해 예술가의 47 %가 학사 학위 이상을 가지고 있습니다.

인종화된 (racialized) 캐나다인은 모든 근로자 (21 %)에 비해 예술가 (15 %)에서 덜 대표됩니다.

예술가들 사이에서 원주민 및 이민 계 노동자가 약간 덜 대표됩니다: 원주민 (예술가의 3.1 %, 전체 근로자의 3.9 %)과 이민자 (예술가의 21 %, 모든 근로자의 24 %).

다른 노동력에 비한 예술가의 소득 격차를 제외하고도 지적해야 할 점들이 눈에 띕니다. 예술가들 사이에 여성 예술인이 더 많고, 예술가들은 교육 수준이 높으며, 예술가들 사이에서 인종화된 (racialized) 캐나다인이 과소 대표되고 있습니다. 이러한 측면은 나중에 면밀한 분석이 필요합니다. 하지만이 프로젝트의 목적 상 아티스트의 소득 불일치에 초점을 맞출 것입니다.

Source: https://hillstrategies.com/resource/statistical-profile-of-artists-in-canada-in-2016/

II. INVISIBLE LABOUR

Why do artists continue to earn less than other workers in Canada?

To answer this question, I think we need to look at the societal perception of labour. We live in a society that values productivity; labour = productivity; productivity = (visible) products; products = money. How do you measure artists’ labour according to this economy of labour?

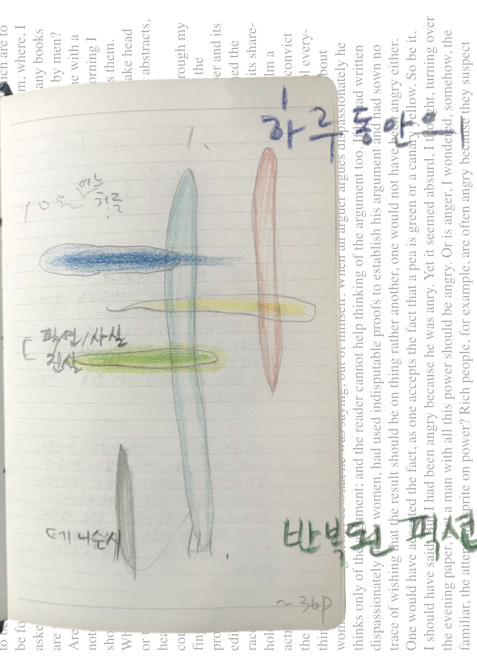

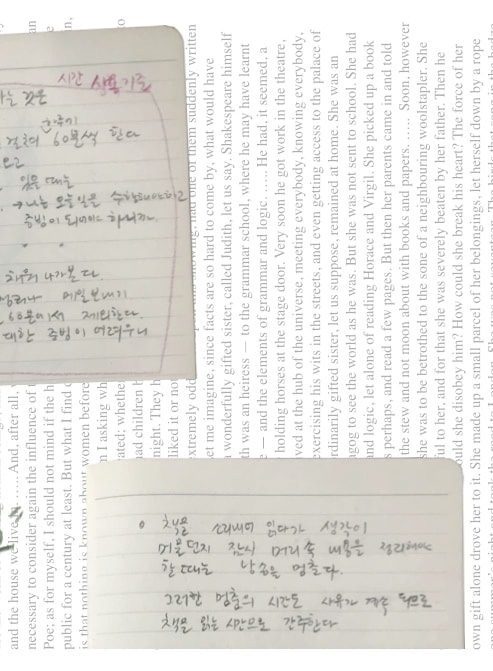

I often work alone in my studio. I spend time researching various aspects pertaining to my art; this could be technical and/or conceptual studies. There are many trials and errors before I can execute the idea. But even then, there are many failed projects that will never be seen by others. For my working process, these failed ideas and hours of contemplation provide a foundation for my art. At the end of the day, I may have nothing tangible to show for my labour. This invisible nature of art-labour might be the cause as to why hours of my labour are not being valued as much as other types of labour. What is visible to others is only a tiny portion of hours of invisible labour.

We proclaim that we love art, that we cannot live without it, and our society is better for it, but do we value the time and labour artists devote to it? And if we do, how do we support the time and labour that goes into making it? And if we don’t, perhaps, this calls for a global artist-strike!

However, a sense of freedom and autonomy can be found in this invisible labour. I don’t have to count my hours for the purpose of transferring to a monetary value; who’s going to pay for my labour, anyway? I am not pressured to make a work that is sellable; this is perfect because I often work in performance and installation. Once my labour becomes visible, meaning there is an expectation of turning my labour into a profit, I am no longer in charge of my own work. There is a price I have to pay for my freedom. I have to keep my precarious part-time gig, so I can continue to wander and work at the same time.

In this book, I want to illustrate the complex web of invisible and visible labour that goes into making an artwork.

II. 보이지 않는 노동

왜 캐나다의 예술가들은 다른 노동자들에 비해 수입이 적을까요?

이 질문에 답하려면 노동에 대한 사회적 인식을 살펴볼 필요가 있다고 생각합니다. 우리는 생산성을 중시하는 사회에 살고 있습니다; 노동 = 생산성; 생산성 = 뚜렷한 결과물; 결과물 = 돈. 이런 노동 경제 틀 안에서 예술가의 노동을 어떻게 측정합니까?

나는 종종 스튜디오에서 혼자 일합니다. 내 작품에 관련된 다양한 측면, 즉 기술및/ 또는 개념에 관한 리서치로 시간을 보냅니다. 아이디어를 실행하기 까지 많은 시행 착오가 있습니다. 다른 사람들이 보지 못할 실패한 프로젝트도 많이 만들어 냅니다. 내 작업 과정에서 이러한 실패한 아이디어와 생각하는 (‘멍 때리는’) 시간은 내 작업에 튼튼한 지반을 제공합니다. 하루가 끝나면, 내 수고에 대해 보여줄 것이 없을 수도 있습니다. 이러한 보이지 않는 예술 노동의 성격이 나의 노동 시간이 다른 유형의 노동만큼 가치가 부여되지 않는 원인이 될 수 있습니다. 다른 사람들에게 보이는 결과물은 눈에 보이지 않는 노동의 극히 일부에 불과합니다.

우리는 우리가 예술을 사랑하고, 예술 없이는 살 수 없으며, 우리 사회가 예술로 인해 더 좋아진다고 선포하지만, 우리는 예술에 바친 시간과 노동을 소중히 여기는지는 궁금합니다. 우리가 소중히 여긴다면, 예술을 만드는 데 드는 시간과 노력을 지원해야 하지 않을까요? 그렇지 않다면, 글로벌 아티스트 파업이 있어야할듯 합니다!

하지만, 이 보이지 않는 노동은 우리에게 자유와 자치권을 주기도 합니다. 내 노동 비용을 지불할 사람이 없으니, 나의 노동 시간을 금전적 가치로 전환하기 위해 계산할 필요가 없습니다. 나는 퍼포먼스와 설치예술을 하는 작가로서, 판매 할 수있는 작품을 만들라는 압박이 없으니 더욱 자유롭습니다. 내 노동이 눈에 보이게되는 순간, 내 노동을 이익으로 전환 할 것이라는 기대가 생기며 더 이상 나는 내 작업에 주인이 될 수 없는 우려를 감당해야 합니다. 당연히 난 내 자치권을 지키기 위해 계속해서 불안정한 시간강사 노릇을 하며 자유롭게 방황 하면서 일 할 수 있는 대가를 지불 해야지요.

저는 이 책을 통해 복잡하게 연결된 보이는 또는 보이지 않는 예술노동 과정을 시각적으로 설명하고자 합니다.

II. Plan/계획/Work

IV. Book

This book is a result of my labour.

This book is a visual representation of collaboration with Choe Ra-yun.

This book is made with the help of Park Jiwon.

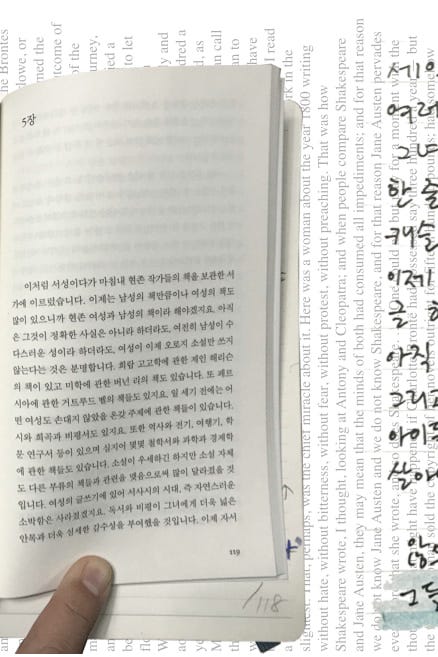

This book is a response to Virginia Woolf’s book “A Room of One’s Own”.

This book is a reaction to society’s lack of understanding of artists’ labour.

This book is a product of my hours of invisible labour.

이 책은 나의 노력의 결과입니다.

이 책은 최라윤 과의 협업을 시각적으로 표현한 것입니다.

이 책은 박지원의 도움으로 만들어졌습니다.

이 책은 버지니아 울프 (Virginia Woolf)의 저서“자기만의 방”에 대한 답변입니다.

이 책은 작가의 노동에 대한 사회적 이해 부족에 대한 반응입니다.

이 책은 눈에 보이지 않는 나의 노동의 결과물 입니다.

June Pak is an artist and educator based in Toronto, Canada. Her personal experience of living in Canada as a Korean-Canadian occupies her interdisciplinary practice. Images in her works are often duplicated, erased, masked, and performed to manifest the complex nature of inter-connectivity between visibility and invisibility of ethnic and racial representation. Her works have been shown in Canada and abroad. She received numerous grants for her projects from Canada Council for the Arts, Ontario Arts Council, and Toronto Arts Council. She is a recipient of the K.M Hunter Artist Award in Visual Arts (2004) and the Chalmers Arts Fellowship for her research on the lives of non-ethnic Koreans in Korea (2017-2019).

Support Send My Love to Anyone

Support Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it!

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

Connect

Bluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA