Strawberry Moon

One of these days we'll both be fine

One of these days we’ll both be fine

Strawberry Moon

When I got to the hospital, one of the patient’s daughters informed me that “Everyone was off today. Your mother too.”

A nursed looked it up and apparently there’s a full moon on June 11—a Strawberry Moon. I don’t know much about moons, but it’s interesting that health care professionals notice changes in behaviour on full moons. While the science doesn’t quite back up the folklore, there have been some recent discoveries around the moon and sleep patterns which could account for some behavioural changes.1 In any case, it was true—everyone did seem off including my mother who was more agitated and distressed than usual.

She didn’t know she was in the hospital and asked why she was wearing a strange dress.

“In some circles those are called hospital gowns,” I said. She laughed and laughed.

Although she wants to wear her normal clothes, my sister and I have decided against it. The one day we tried, she demanded to see the manager about leaving.

The hospital gown—although distressing—grounds her to place so it’s easier to explain to her she’s in the hospital.

*

After dinner we went for a walk.

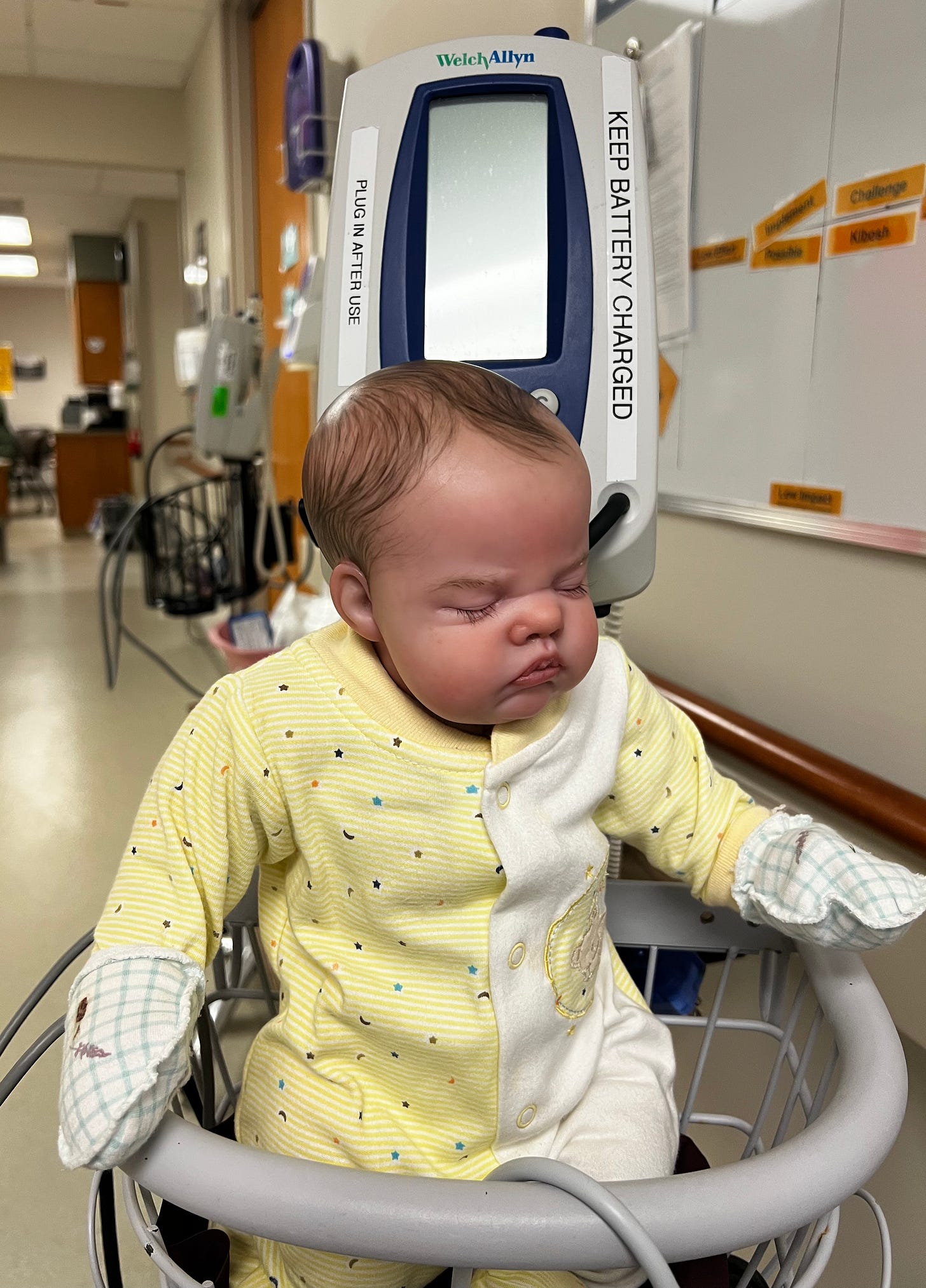

This hospital ward has a doll that looks like a live baby which confuses my mother every time she sees it.

“Is that a real baby?” she asks.

“No,” I say. “It’s to comfort some of the patients.”

In the TV room at the end of the hall, they have a basket of baby clothes that the patients can fold. One day I asked my mother if she would like to fold these baby clothes knowing full well she would not.

“Ah, no,” she said. “Why would I want to do that?”

Doll therapy for Alzheimer’s patients has some benefits but also there are ethical issues.2 While it can calm patients, there is concern that it diminishes the dignity of the person with Alzheimer’s by treating them like a child when they are not a child.

As we walked through the hospital corridor, the doll was sitting precariously on a chair. My mother looked at it in concern. I couldn’t tell if she was trying to make sense of it or if her social worker self was assessing whether or not the child was in danger. My mother was an intake social worker and later an abuse specialist.

A psw was nearby when I said, “Don’t worry, Mom, that’s a doll not a real baby.”

The psw said, “Some patients like it, so don’t tell them it’s not real.”

“I do not like dolls,” my mother said, and we all laughed. I hoped it was clear no one should be putting that doll in my mother’s arms.

There is not much I can do for her in these terrible times, but I can try to preserve her dignity.

*

Later back in her room, we did some easy crosswords. I’m pretty bad at even the easiest crossword puzzles, so I find a question I think would be fun for my mother, look up the answer, and then give her clues until she gets the right word.

Often she doesn’t even need the extra clues like when I asked her the name of a witches’ group—my mother blurted out “coven,” without a second thought.

“I don’t know why but that just came right to my head,” she said. I could tell this made her feel good.

One thing that distresses her about her memory loss is that she doesn’t feel smart, and this game makes her feel intelligent. My mother doesn’t have a lot of hobbies, but one thing she loves is trivia. She used to have a photographic memory and was very good at Jeopardy and Trivial Pursuit.

After the crosswords, we played some games of tic-tac-toe to pass the time.

“I don’t like it here,” my mother said.

“I know.”

“What am I going to do with my life?” she asked.

“You’re moving to Toronto to be closer to all of us,” I said. “Would you like that?”

She nodded.

*

Full moon or not it was difficult to get her to settle in. She needed her gown adjusted and her socks removed. It took her forever to find a good position in the bed, and then the noise of the room disturbed her. There are four beds in this room, and everyone is hard of hearing (except my mother), so visitors, nurses, and psws have to speak louder than usual. When there is activity at all four beds, the room sounds like a busy restaurant or bar.

We did some breathing exercises. Then I told my mother to shut her eyes and I would leave when she was asleep. She would shut her eyes for a moment and then open them to see if I was still there.

“You’re going to leave when my eyes are closed,” she said laughing.

“I won’t leave until you are asleep,” I assured her.

As I stood by her bed and watched her try to fall asleep, I was struck by a flashback from my childhood.

*

I was five, and it was a few months after my father had left. My sister who was twelve was at a friend’s house for dinner. I had been playing in my room and realized I was hungry, so I searched for my mother. She wasn’t in her yellow chair in the living room watching TV, but a cigarette was smouldering in the ashtray, which I didn’t think was good so I put it out. Then I found her sleeping in bed.

I called to her and tried to shake her awake, but she didn’t move. I thought she was playing, so I shook her again and again. I lifted her arm, and when I let it go, it fell flat. I pinched her. I slapped her. But she was unresponsive. I listened to her chest to see if her heart was beating. It was. I checked to see if she was breathing. She was, which gave me some momentary relief.

She wasn’t dead. Yet.

I pulled back her eyelids but could only see the whites of her eyes. It was terrifying.

I wept. I screamed. I begged her to wake up. This was the first time in my life that I was truly frightened. There was something terribly wrong with my mother. Was she sick? Was she dying? I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know to call 911. I didn’t know my father’s phone number. So I curled up on the green carpet beside her bed and sobbed.

About an hour later, I heard my sister open the front door. I yelled out that Mom was sick.

My sister came into the bedroom and looked down in disgust at our mother passed out on the bed. She went to the kitchen and calmly grabbed a cup of water. When she returned, she threw the water on her face and called her a fucking bitch.

Our mother awoke disoriented, her pillow water soaked. Then she fell back into her stupor.

“She’s drunk,” my sister said. “She did this to herself.”

I remember being confused at the concept that someone would do this to themselves. I didn’t even really understand what it meant to be drunk or why my sister was so angry.

“Have you eaten?” my sister asked.

I shook my head, and we went into the kitchen where she made me a grilled cheese sandwich.

*

My mother never did get to sleep before I left the hospital.

After a few rounds of me asking her to close her eyes and her opening them, I set her up with a game of Solitaire on her iPad before heading out for the night.

“You think that will work, do you?” said the woman who addressed me when I first arrived.

This woman is there morning til night with her mother—something I just cannot do. When my mom was first admitted to the hospital we were there for long stretches of time, but it was not something we could keep up.

Care-giving, I realized, must be done imperfectly.

I turned to my mother and said, “I love you,” and squeezed her hand.

“I love you too,” she said and returned to her Solitaire game.

On the walk home, I meant to watch for the Strawberry Moon but forgot to look up.

Read more from One of these days we’ll both be fine

Kathryn Mockler is the author of Anecdotes.

Consider donating to Crips for eSims for Gaza.

Support Send My Love to Anyone

Support Send My Love to Anyone by signing up for a monthly or yearly subscription, liking this post, or sharing it

Big heartfelt thanks to all of the subscribers and contributors who make this project possible!

Connect

Bluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA

“Moonstruck.” How Myths of Lunar Power Continue to Fascinate Us: Kate Golembiewski Explores the Long History of Associating Madness With the Full Moon, November 20, 2024, https://lithub.com/moonstruck-how-myths-of-lunar-power-continue-to-fascinate-us/

Pros and Cons of Doll Therapy in Dementia by By Esther Heerema, MSW Updated on February 05, 2025, https://www.verywellhealth.com/therapeutic-doll-therapy-in-dementia-4155803

The telling of this moment and the memory between are so smooth. I could see it all play out effortlessly. I am sorry for you and for your mom. You are such a good daughter. I hope you are able to bring her into a better living arrangement soon! I love the last line expressing your wanting to look at the moon but forgetting to look up. So, poignant! It's the perfect emotional sentence to end this piece on.

Beautiful, Kathryn.